a reflection on disappearanceText by Christopher Squier

October 2024

The Harriman Institute at Columbia University

co-organized with The Russian American Cultural Center

presents Michel Gérard & Marina Tëmkina: Children of the War

October 28 – December 12, 2024

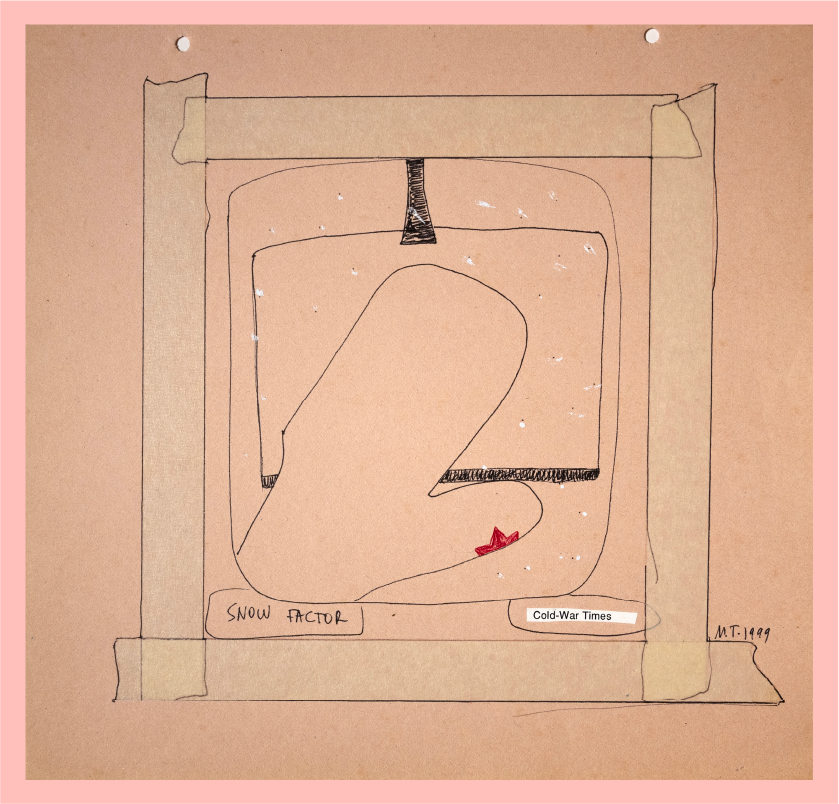

A dusting of snow settles on the taupe brown of the page, concealing the speckled fibers. It covers the ground with a combination of jet black ink and pellucid snow. If any antique marks, foxing, or fingerprints had left stains on the page over the past twenty-five years, this flurry would diminish them, eventually effacing the entirety of the image. But within the instantaneous moment preserved here, we observe only the onset of the storm: the barometer dips, clouds pile in, and flakes of snow crystalize out of the empty air.

Cold War Equipment, a diptych of drawings by the poet-artist Marina Tëmkina, stops the viewer cold—even snows one in, leaving us peering from behind the hoarfrost of a window frame at the crystalline images within. One image is outlined in the bubble-like square common to many of Tëmkina’s drawings of this decade; the other is limned in the glossy faded yellow of masking tape, torn and applied in a grid of cross-linked studs like the timber frame of a wooden box or house. The sight is familiar, although its subject is disembodied. A hat and a single mitten hover in the center of each page, as if in a department store ad offering up this season’s winter wares. There is no accompanying head nor hand to fill them out. In the drawing of the mitten, three red triangles spring from the knuckle of the thumb like a cartoon injury, a blood red chunk of flesh oozing before a scab can form. The hat reveals this constellation of triangles as the five-pointed star of the Communist Party, another ornament-become-injury like a bloody spot on the forehead. Against the snow and the neutral browns of the paper, the sanguine red of the two stars demands attention. In an art historical context, the scene might be read as one of holy relics. But in a strictly historical sense, it recalls a less divine history of violence.

The political and military overtones of the scene would be apparent to the post-Soviet and emigrant communities familiar with these garments. The hat, an ушанка (ushanka), and the mittens, варежки (varezhki), were part of the common winter uniform given to Soviet soldiers, distinguished from civilian clothing by the symbol of the Party. Tëmkina has added collaged elements of printed text to situate us in the era of the Cold War and remind us of the military advantage winter has long been said to offer the Russian-Soviet army: “Snow as a strategic factor” reads one cut-and-pasted text. The detail that charms and fascinates me most about these works, which are as charming as they are devastating, is that the snow obscuring the composition is painted with Wite-Out correction fluid, a simple, nostalgic material that draws up bygone days of writing essays by hand: the sharp, almost acrid smell of the opaque fluid, the clumping globs of dried liquid snagging on the rim of the bottle, the soft scraping sound of the tiny foam applicator brush. Applied on the substrate of brown paper, these small moments of disappearance stand out all the more, forcing what was meant to be disguised to show itself to us.

In Tëmkina’s Cold War Equipment, the combination of text, Wite-Out, and drawn image meets on the surface of photo album pages. Throughout the 1990s, many of Tëmkina’s drawings were made on this particular paper, which she discovered at a wholesale store and began using repeatedly. “This paper is not the precious art paper for drawings,” she tells me. “This is a photo album, a domestic object (female). It has time, age, memory, emotional-sentimental value … [the paper] is a color used in Renaissance drawings as well as a color of everyday activities such as shopping in the supermarket, brown bags. The combination of high and low I liked always.” The substrate ties the work to ideas of biography, personal history, and reminiscence; it also points us toward the personal impact of U.S.-Soviet tensions and nuclear proliferation on the lived experiences of citizens on both sides of the conflict. The politics of the era became inscribed indelibly within the lives of immigrants like Tëmkina, who fled the U.S.S.R. in 1978 when political stagnation seemed to penetrate all spheres of Soviet society. Not long after arriving in the U.S., her first New Year’s celebration brought news of the Soviet war in Afghanistan. Making drawings about these conflicts two decades later, I suspect that Tëmkina includes the Soviet military’s hat and mittens on photo album pages to suggest the personal echoes of these objects, how they spur memories of past wars and political epochs.

Earlier in the century, Joseph Stalin and the N.K.V.D. had notoriously effected the disappearance of citizens, not to mention the erasure of personal memory in favor of official histories. These official histories themselves became mythologized, inflated by state rhetoric, so that eventually the idea of objective truth would flicker out of visibility. However, in Cold War Equipment, the Wite-Out correction fluid functions on the contrary as a marker of memory, a clarifying and identifying mark making disappearance visible. In allowing dots of Wite-Out snow to wipe out the image, Tëmkina references how facts and headlines seemed to disappear without being accounted for. The series marks the unsettling feeling of a sudden disappearance, as when the Cold War abruptly came to an end in 1991, fading from newspaper headlines and everyday conversations. As Tëmkina tells me, “The Cold War appeared/disappeared as well. It seemed like that in the ’90s.”

I’m amazed by the simplicity of this gesture. The two drawings utilize the intimate format of the photo album and the ordinary materials of a writer—pens, stationary, a printer, Wite-Out, and masking tape—to address the preservation of memory in the face of wars, whether hot or cold, state sanctioned or internationally denounced. The drawings satirize the idea of the U.S.S.R. as a well-functioning superpower in the latter half of the 20th century at a time that its economy, agricultural sector, and industrial manufacturing faltered. As Tëmkina notes, “These two drawings for my compatriots look like a humorous description of the Soviet military reality—all they had and all that worked were these hats and mittens.”

Another of Tëmkina’s projects from the same decade, The Kitchens Where I Cooked, is shown here, thoughtfully juxtaposing her numerous creative approaches to post-Soviet immigrant life. The photo series is captured on black-and-white film with a camera. The speckled grain of the film adds a texture of analog media to the images, echoing the artist’s eye for the prosaic textures of life that remain behind in historic spaces. One image that draws my eye (and coincidentally, one of the first two images created in the series) shows the intimate space at the former home of Marina Tsvetaeva’s half-sister Valeria in Tarusa, Russia. Tsvetaeva, one of the most salient Russian modernist poets, used to spend summers in Tarusa in her youth. She wrote about her experiences in numerous poems as well as one short story, « Хлыстовки » (“Khlystovki”). Tsvetaeva’s daughter Ariadna Efron lived in the same house upon returning from sixteen years of internal exile. Following Valeria’s death, the house in Tarusa was purchased in order to be preserved.

Tëmkina had the occasion to visit Tarusa when she received a grant from ArtsLink for an exhibition and poetry reading at the studio of Ilya Kabakov, then the site of the Institute of Contemporary Art in Moscow. She flew to Russia to mount the exhibition in the summer of 1998. Some days before the installation began, she and Gérard received an invitation to join a bus trip to Tarusa for a memorial concert honoring classical pianist Sviatoslav Richter and his wife Nina Dorliak, a singer and a professor at the Moscow Conservatory. Tëmkina confides that the invitation allowed her to realize her dream of visiting Tarusa. The dinner following the concert was held at Tsevaeta’s home. As is so often the case, the owners’ care for the house amounted to the bare minimum. As a result, the house and kitchen struck Tëmkina as a reminder of the painful circumstances of Tsvetaeva’s life. During the dinner, a fish soup was served, prepared in the white enamel bucket seen in the photographs. The assembled guests made toasts around folding tables in the garden, not far from the bank of the river where the fish for the meal had been caught. Everything about the evening is contained within the two photos of the crowd and the kitchen. The magical thing about Tëmkina’s photographs of the evening is how they juxtapose sounds and energy: the crowded garden full of boisterous guests set against the stillness of the kitchen and its array of cooking implements, drying racks, and appliances. If she’d arrived a moment earlier in the kitchen, it might still have been in use, a site of chaos, but Tëmkina manages to bestow it with a momentary reprieve of the sort Tsvetaeva herself may have found there amidst the drastic turns of her life.

Each of the photographs from the series is connected to an experience of conflict or creation. One photograph was taken at the former military garrison at Plasy, Czech Republic, a site which was abandoned by the Soviet Army after the collapse of the Soviet Union. Compiled over five years, Tëmkina’s intimate documentation of these kitchens underscores the relationship between private and public, personal and political. One imagines small details: olfactory memories of wafting scents, the resourcefulness of scraping together a meal, and above all, the passage of time.

The exhibition pairs Tëmkina’s work with that of her husband, the French sculptor Michel Gérard, connecting the stories of two historic moments in Russia and France (or from Leningrad to rue de Leningrad in Paris, as the artists put it in the title of their two-person show). The theme of translating conflict resurfaces in Gérard’s work, whose series of drawings Boys Fight is adapted from an illustrated entry of the Nouveau Petit Larousse Illustré. The Petit Larousse was a long-standing French-language dictionary that Gérard’s family, like many others, owned when he was a child. During the occupation of Paris, before he could read, Gérard would look at its pictures.

In 1990, the artist discovered a copy of the dictionary and began reworking imagery from its pages, especially the images of French sports games and boxing techniques. Although presented as educational in nature, the pages on boxing offer an elaborate reconstruction of each jab, hook, and parry with step-by-step definitions of the actions. Drawn while the artist was recovering from a surgery, these drawings seem to me to contemplate the passage from youthful energy through the inevitability of aging. It’s also worth noting that Gérard worked from the 1942 edition of the Petit Larousse, a volume produced during World War II; here, he casts its illustrations of boxing matches as a reminder of the detrimental effects of conflict from the vantage point of a child.

Fifteen of these drawings are included in Gérard and Tëmkina’s recent artist book Boys Fight. Within each composition, the fiery circular explosions of red-orange nebulas radiate in the background, framing the action of the boxing match; meanwhile, lines of motion vibrate from the combatants’ arms, backs, and legs. Fighting is reframed within this red-hot arena; it becomes a celestial occurrence, something larger than the scale of human life with the kinetic dynamism of stars colliding. As each boxing movement is repeated ad infinitum, the works operate like a flipbook animation, pointing us frame-by-frame toward the process of watching, learning, and reproducing violence, even in safe and sporting forms. Similarly, the visual reference to cavemen and dinosaurs in the accompanying series Self-Portrait as a Caveman extends the arena of aggression to time immemorial.

Tëmkina’s lines of poetry invite interpretation of Gérard’s drawings during a more recent period of political warmongering. Her poem “Boys Fight” was completed in 2015, following the first Russian invasion of Ukraine the year prior. As she wrote the lines of the poem, she remembers listening to the pugnacious language of the U.S. presidential campaign. The two coinciding political events prompted her elegy for the pain of endless wars. In the poem, Tëmkina’s cycling phrases repeat her feminist and anti-war lament as though it were a mantra, applying it in different contexts, across continents and time, until one unavoidably sees how combat has inundated the history of human achievement, social relations, and identity. The poem and other texts by Tëmkina are presented alongside the exhibition. They are worth reading, and worth re-reading, as our world leans into new conflicts that will likely define our own era of aggression.

Visit:

Harriman Institute Atrium

Columbia University

420 W 118th St, 12th Floor

New York, NY 10027

Monday–Friday, 9:00 AM–5:00 PM by appointment only